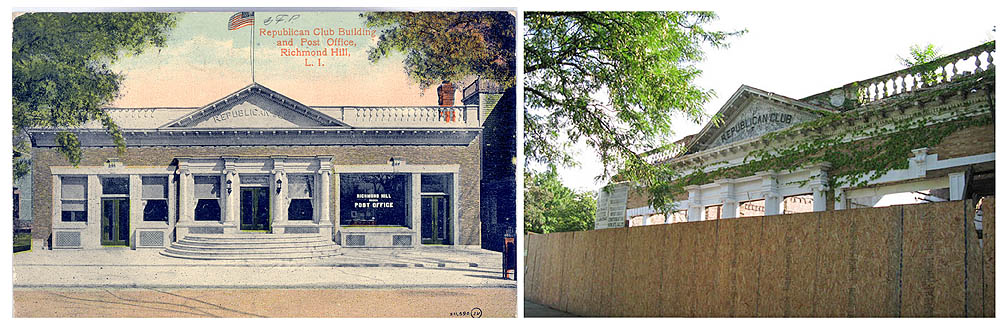

Demolished: 2006

History: In 1883, Henry Gurdon Marquand, a banker, railroad executive and among the founders of the MET, began his private stable at 166 East 73rd an unusual work by the architect Richard Morris Hunt. This block of 73rd Street became one of the most populated stable streets in New York.

Marquand died in 1902, and his estate sold the stable to the publisher Joseph Pulitzer, then just completing his own mansion at 11 East 73rd Street. When Pulitzer died in 1912, his $17 million estate included the stable, valued at $68,000, with two brown mares appraised at $125 and $100, a bay at $65 and a chestnut horse at $75. He owned no automobiles, but had three carriages: a landau worth $50, a victoria worth $40, and a hansom worth $10.

In 1924 the MacDowell Club — an institution supporting the MacDowell Colony, the artists’ retreat in Peterborough, N.H. — bought the old Marquand stable. In 1979, the Landmarks Preservation Commission included the Marquand stable in an area landmark designation in 1981. Robert and Ellen Kapito bought the building for conversion to a two-family residence and have embarked on a most unusual effort. After chipping off the stucco and exposing the raw, damaged brick, they are planning to have it sanded down to reveal the original deep molten red. It is rare to see a building so fully resurrected from so deep a grave.

Adapted from the New York Times (Christopher Gray, June 3, 2007)Full story: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/03/realestate/03scap.html

Wood: Antique Long Leaf Pine / 2 1/2 x 11 x 12′+

Photos: (l) nytimes.com (r) Melanie Einzig