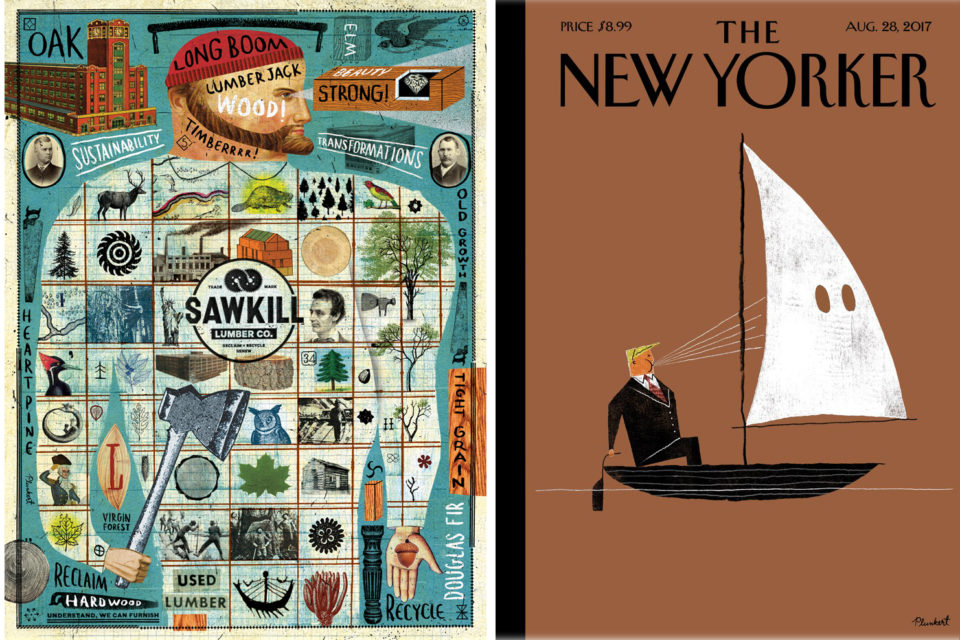

Congratulations to Dave Plunkert, who produced our lumberjack illustration, and let his work set sail this week for the New Yorker with “Blowhard”.

The Tree

Working with Reclaimed Wood

Course No. 001

Working with Reclaimed Wood

Participants will be guided through basic woodworking skills that make use of hand and power tools to construct side or coffee table from reclaimed wood. The class also introduces the sources of the woods – both forest origin and the historical structure – along with finishing options, safety considerations, and a review of available leg options.

Featured reclaimed woods include NYC heartwoods, Barn hardwoods, Redwood storage tank and the Coney Island Boardwalk

Tuition: $175 + material (ranging from $40 to $100)

Time: Sat./Sun 10-2 pm

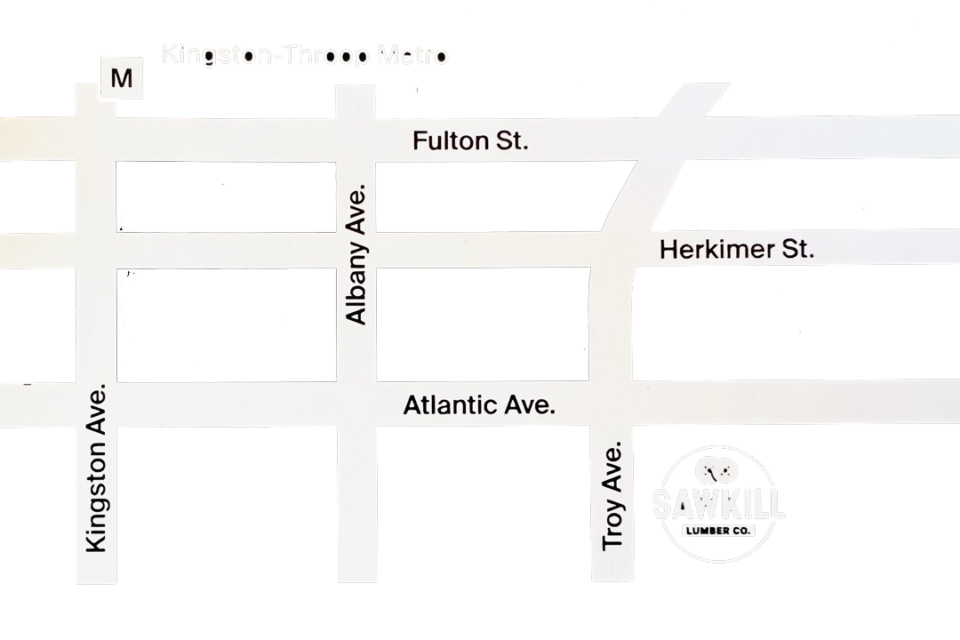

Location: Sawkill Lumber – 71 Troy Ave. Bklyn Trains: A, C to Utica Ave.

Class size: 6

Sign Up

Lightning Strikes & Reclaimed Pine

Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata)

Shortleaf Pine can be an apt name when it comes to it’s role in the city’s early built environment, relative to the more celebrated Longleaf Pine, which was an important wood for framing commercial structures, due to it’s heavily resinous grain, providing great strength, and resistance to fire and bugs. By the time Southern lumber companies doubled back for the broader and less resinous Shortleaf Pine, NYC was starting to gain more access to Western Douglas Fir and could make-do with other conifers. Shortleaf entered the mix nonetheless, though it can be hard to distinguish from it’s counterpart, Loblolly (Pinus taeda), so that both exist in varying lumber volume, essentially from the beginning of the modern era in the 20th century.

Shortleaf Pine can be an apt name when it comes to it’s role in the city’s early built environment, relative to the more celebrated Longleaf Pine, which was an important wood for framing commercial structures, due to it’s heavily resinous grain, providing great strength, and resistance to fire and bugs. By the time Southern lumber companies doubled back for the broader and less resinous Shortleaf Pine, NYC was starting to gain more access to Western Douglas Fir and could make-do with other conifers. Shortleaf entered the mix nonetheless, though it can be hard to distinguish from it’s counterpart, Loblolly (Pinus taeda), so that both exist in varying lumber volume, essentially from the beginning of the modern era in the 20th century.

Shortleaf has an ability to grow on a wide range of soil and natural conditions. While an NYC resident today (in the most literal sense), it was formerly a home and food source for a range of wildlife – quail, doves, meadowlark, rabbits, songbirds. white-tailed deer, and of course the red-cockaded woodpecker.

Basic Shortleaf and Loblolly uses include lumber, plywood, and pulpwood for paper. It’s easy to work and takes a stain and paint well.

Oak (Quercus alba)

New York is also a tale of two woods – Oak and Pine. Hardwood and softwood, furnishings and structural applications, Higher and lower values. Pine and other softwoods for framing and Oak for floors. Though all this can seem turned around for good reason in these post-modern times. But the two woods can seem as close and distant in their vision of what a wood can and should be as a Blue State and a Red State, though they co-exist well.

New York is also a tale of two woods – Oak and Pine. Hardwood and softwood, furnishings and structural applications, Higher and lower values. Pine and other softwoods for framing and Oak for floors. Though all this can seem turned around for good reason in these post-modern times. But the two woods can seem as close and distant in their vision of what a wood can and should be as a Blue State and a Red State, though they co-exist well.

In ways that’s understandable, the two evolved as a species eras apart on the earths timeline, with Oak not arriving until after the dinosaurs, and developing a more complex cellular structure in relation to the more Classical model of Pine fibers. But the wide use of the two woods has been a material reality of New York since the earliest European settlers climbed out of holes they dug for winter shelter when first arriving.

In Colonial times, Pine was as emblematic of statehood and the nation as the bald eagle and Apple pie. A pine tree is even featured on the earliest American flag. Their forests seemed so limitless, and carried the quiet dignity of most any tree, and found ubiquitous use in products of all description. It was a tree well suited to the growth of a young Democracy.

Oak was European, and though it was logged in massive quantities throughout all the New England states, it has deep cultural roots in European civilization, along with other hardwoods. It wasn’t a Pine cone that dropped on Newton’s head. It was most likely “The knights of the round Oak table”. And Oak vessels carried the guns that built an Empire. It’s the national symbol for at least six European countries.

Over time, Oak – Red and White – would make more inroads into the American imagination and home. Prosperity, cultivation of the species and advances in woodworking machinery all played a role. So that today, Oak can not only feel as “made in America” as any wood – it was declared by Congress in 2004 as the National Tree – even if the bulk of it comes out of Canada.

Oak is a dense wood, with great strength and hardness, and is very resistant to insect and fungus. It has a very attractive grain to many people, including kings and queens of the Middle Ages, especially when quartersawn. But it can also be royal pain in woodworking, being prone to severe movement when not properly dried.

Of the 500 species of Oak in existence, over 75 now are threatened by extinction, and the numbers may be much greater, since limited information is available for many species. The U.S. is native soil for just one percent, or five, of the Oaks in existence.

Cypress (Toxodium distichum)

Cypress or Bald Cypress (Toxodium distichum) originated in the dense swamps of the South, slow growing – among the slowest aging trees on earth – for up to seven hundred years. The tree is a haven for a range of species; migrating Canadian geese feed on the seeds, along with swamp rabbits and other birds. White-tailed deer make the Cypress forests a refuge during hunting season, where many other animals find shelter.

Cypress or Bald Cypress (Toxodium distichum) originated in the dense swamps of the South, slow growing – among the slowest aging trees on earth – for up to seven hundred years. The tree is a haven for a range of species; migrating Canadian geese feed on the seeds, along with swamp rabbits and other birds. White-tailed deer make the Cypress forests a refuge during hunting season, where many other animals find shelter.

Cypress is versatile, rough-sawn or smooth; it takes nearly every surface treatment around. With it’s rot resistance and rich color, from off-white to deep red, it’s a warm and elegant wood for interior paneling as well as exterior decking.