A 'Design' Tempest in Brooklyn

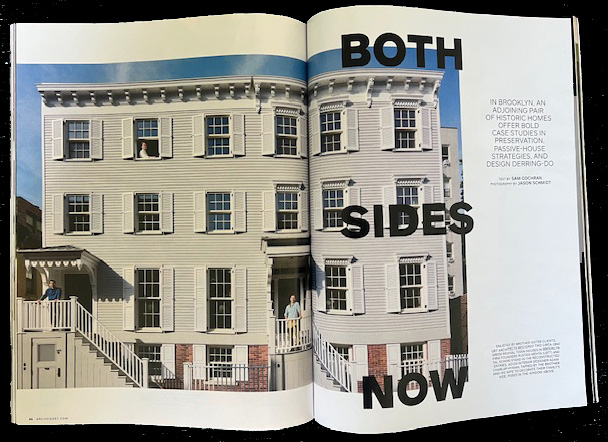

A pair of circa 1830’s attached homes on a quiet block in Brooklyn’s Clinton Hill neighborhood restored the facade to landmark standards, removed all but the interior bones and then pulled off an outside the box suspension of the house for foundation work. It was featured on the April cover of Architectural Digest Magazine.

From the outside, the houses mirror the 1940’s New York tax photo record—modeling the shutters, cornices, and clapboard. Inside, there’s something else entirely – a kind of kaleidoscope mix of historic and modern forms that can feel like their twisting, softening, and coming back together into a unified design against the backdrop of the antique white pine floors and central staircase, with the millworker supplied by Sawkill Lumber.

The project, undertaken by GRT Architects for a brother-sister client, had to satisfy both New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission requirements and a high bar European passive house model. The original building was dilapidated, but the bones had potential. GRT brought on master builders Mark Ellison, Adam Marelli, and Bob Chan of Vision Build to bring it back to life.

On the landmark details, the team approached the restoration with precision. Cornices, shutters, lintels, and siding were all matched to historical documentation, with subtle variations distinguishing the connected homes. The blocks brick rows and existing carriage houses suggested that the immediate neighborhood skewed working-class, and ran parallel to Vanderbilt Ave’s larger homes. Ornament was likely added gradually.

Inside, GRT and the team pushed the boundaries of design and craft. Ellison, known for what The New Yorker magazine called the “impossibly built,” seemed to realize that in the sculpted plywood spiraling staircase. The alternating curves can seem like a collaboration between 1840s New York furniture maker Duncan Phyfe, the Italian mathematician Fibonacci and Frank Lloyd Wright. The staircase anchors the house, like a spiraling energy at its core. It’s not just beautiful—its precision required decades of experience.

That flow of sculptural and design reference carries into the rest of the home – a mosaic “tempest” bathroom to the mid-century chairs beneath Victorian floral lighting, the design lives in the tension between time periods. Adam Charles Hyman’s interior design is a study in “the blurriness of things,” including pieces by William Arthur Snill, Ficus Interfaith, and others that blended old and new, organic and geometric, visual and even literary- moving between Edith Wharton and Gertrude Stein like the shadows from the rear open views.

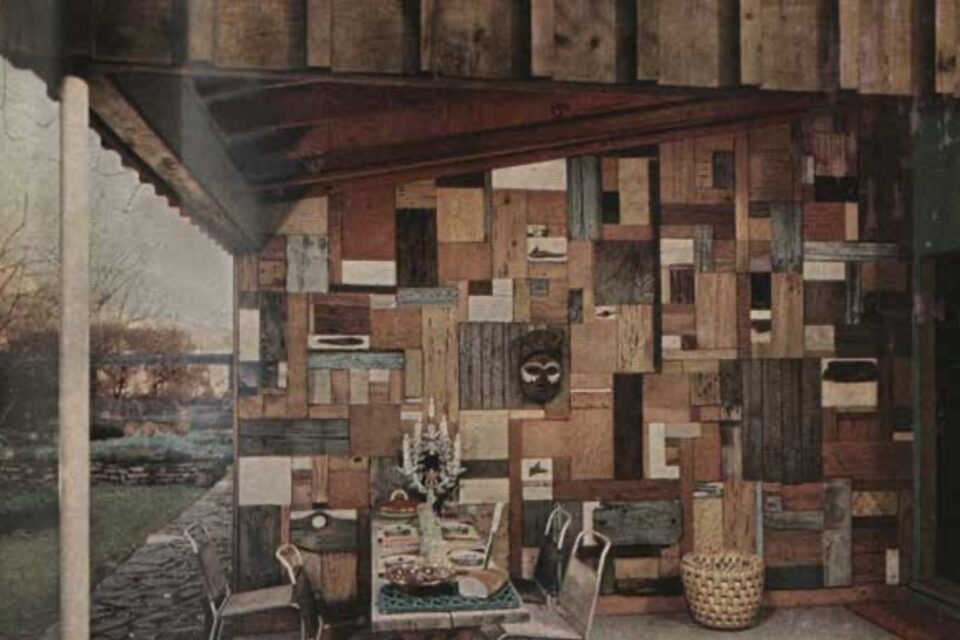

Time Made Visible

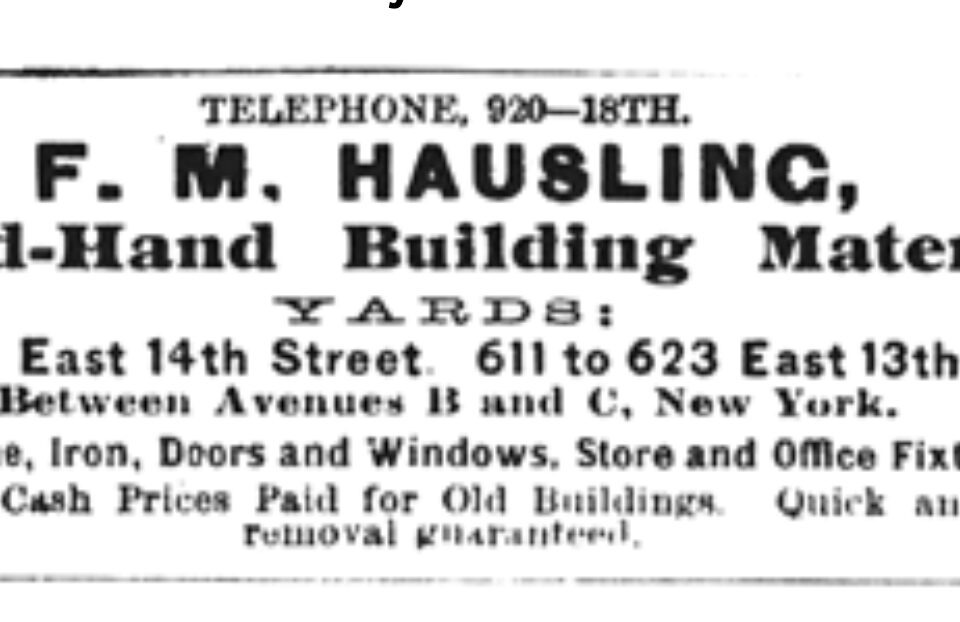

Materials play a central role in this story. A large volume wood was salvaged directly from the home—with some of the beams and floorboards pulled, de-nailed, and re-milled. Where the original material couldn’t be reused, reclaimed wood from Sawkill Lumber filled the gaps, particularly for stair treads and replacement flooring. It wasn’t only a token amount of accent salvage—It was a foundational part of the interior space, integrated into nearly every room.

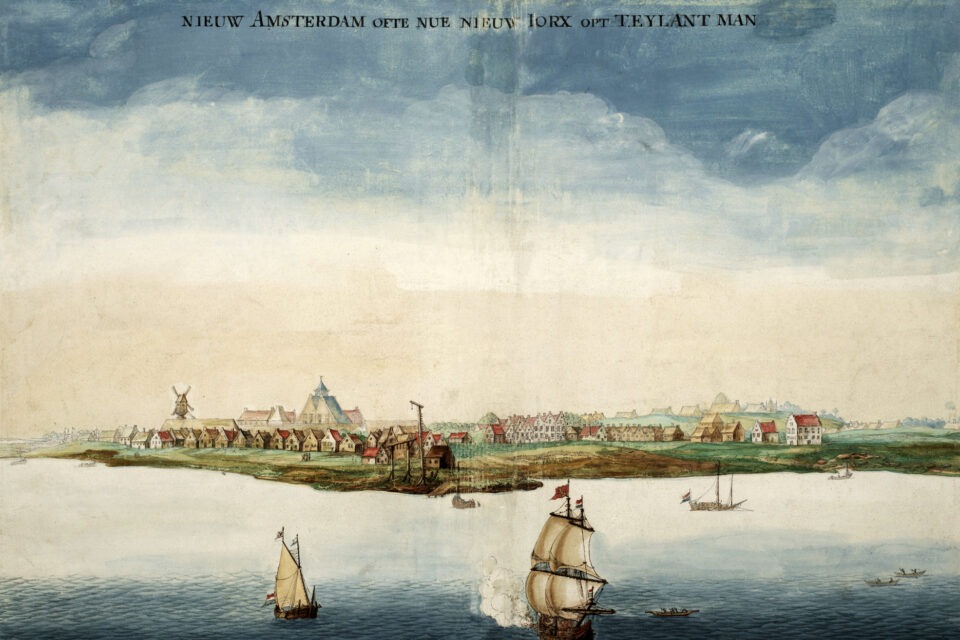

The homes date to the 1830s—nearly fifty years before the Brooklyn Bridge. At the time, Clinton Hill was still a developing neighborhood, with shipbuilders, merchants, and workers drawn to the Brooklyn Navy Yard. New York saw explosive growth after the opening of the Erie Canal, and timber—especially Eastern white pine—was arriving by boat and barge from the Adirondacks and along the East coast to meet demand.

The floors and staircase treads in this home are made of that same Eastern white pine. Some were salvaged from the structure itself as mentioned, while others came from reclaimed material sourced from a building on lower Broadway in Manhattan. Wide, clear sections of pine were re-milled and integrated back into the house in ways that bridge centuries.

Eastern white pine, being a staple of early New York construction (the first block north of Wall Street is Pine Street), is not surprising to see in the house. But what is unlikely that it’s a softer wood, far less dense than oak – but it has held up remarkably well in historic homes for centuries. Over time, pine develops character and depth from wear and layers of shellac and beeswax, and light – the marks of wear on its surface reflect time and are not seen as flaws. In this project, the pine doesn’t merely suggest history—it embodies it. The wood carries memory; a reclaimed connection with the past.